By James Quansah, Pastor

THE MODERN Christianity is characterised by the culture of clericalism in which ordained ministers are viewed as having unquestionable ecclesiastical power and exclusive ministerial responsibility over the rest of the community of believers called the laity.

This has affected the greater majority of the community of believers to relegate their priestly and ministerial duties to the background.

Peter Daly in an article entitled, ‘Tackle Clericalism First When Attempting Priesthood Reform’ published in the National Catholic Reporter magazines states that clericalism is a disease which is deeply ingrained in Christianity.

He argues that “clerics are often trained to think they are set apart from and set above everyone else in the church. Their word is not to be questioned. Their behaviour is not to be questioned. Their lifestyle is not to be questioned. They rule over the church as if they were feudal lords in a feudal society.”

“That is how they see themselves – lords of the manor, complete with coats of arms, titles of nobility and all the perks that go with “superiority.” But Daly does not criticise clerics only as being clerical; he also attacks the laity for fostering clericalism by always deferring to “Father” and putting “Father” on a pedestal.

Pope Francis corroborates Daly’s view in a message when he states “clericalism, whether fostered by priests themselves or by lay person, leads to an excision in the ecclesial body that supports and helps to perpetuate many of the evils that are condemned today. To say “no” to abuse is to say an emphatic “no” to all forms of clericalism.

Thus, Pope Francis sees clericalism as an approach that not only nullifies the character of Christians, but also tends to diminish and undervalue the baptismal grace that the Holy Spirit has placed in the heart of our people.

Moreover, Professor Emmanuel Asante, in the Preface of his book, writes, “There is no doubt in my mind that theologians have given exclusive theological attention to the ministry of the clergy to the neglect of that of baptised believers.”

In what appears to be a commentary on the words of Jesus Christ as recorded in Matthew 9:37, Asante states that the harvest is, indeed, plentiful and the labourers are few because there is a great neglect by theologians regarding the distinctive roles of baptised believers – meaning, in the Christian Ministry, baptised believers have relegated their ministerial calling and responsibility to the ordained, the clergy.

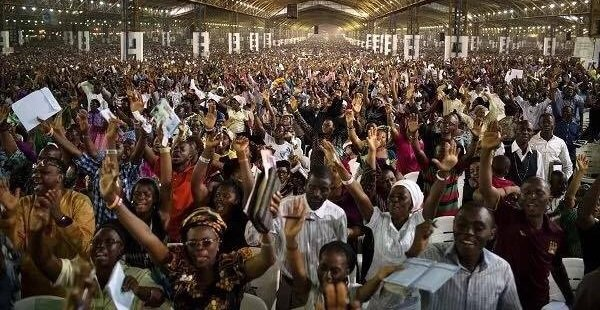

Rick Warren seems to confirm Asante’s view when he opines that “…the church is a sleeping giant. Each Sunday, church pews are filled with members who are doing nothing with their faith except “keeping” it. The designation “active” member in most churches means those who attend regularly and financially support the church.”

He continues, “Not much more is expected. But God has far greater expectations for every Christian. He expects every Christian to use his or her gifts and talents in ministry. If we can ever awaken and unleash the massive talents, resources, creativity, and energy lying dormant in the typical local church, Christianity will explode with growth at an unprecedented rate.”

But should the believers be blamed for shirking their ministerial responsibilities? Have they been equipped, perfected and made suitable for the work of ministry as Paul, the apostle, implored church leaders to do in his epistle to the church in Ephesus?

Certainly, church members’ commitment to ministry largely depends on the equipment they receive from apostles, teachers and bishops. Thus, Warren asserts that pastors must set up a process to lead people to deeper commitment and greater service for Christ – one that will move your members from the committed circle into your core of lay ministers.

But this commitment can hardly be achieved in the prevailing culture of clericalism in Christianity today. Clericalism, in the words of Prof. Darryl M. Erkel, has done much to harm and weaken the body of Christ. It clearly divides the Christian brotherhood; it hinders the saints from behaving like the ministers they are; it obscures, if not annuls the essential oneness of the people of God.

Asante shares the notion expressed by Erkel as he insists that clericalism is a mistake and must be corrected. In his work, Asante points out that “… the twentieth century has seen some momentous changes which had serious effects on the ministry. These momentous changes have also led to the clericalism of Christian service which has limited ministry to that of the ordained.”

It is a fact that in Christianity all believers are Christ’s sheep. Thus, sheep shepherd sheep. In other words, apostles, prophets, evangelists, pastors and teachers who have a charge to tend and feed the multitude of believers are not special and superior as they themselves are fundamentally sheep.

But if a culture of clericalism is created and allowed to grow in the church and create a division and splits its oneness as clergy and laity, then a problem is at hand. And if the harvest is plentiful but the labourers are few as Asante points out, then a culture of clericalism which undermines the priesthood of all believers thereby influencing them to shirk their ministerial duties and feel apathetic to exercise their Spirit-given gifts and talents for the attainment of God’s purpose for the church is problematic.

clcgh.org Building The Capacity Of Christian Leaders, Equipping The Saints For The Work Of Ministry, Redirecting Straying Christians To The Sound Knowledge Of Christ

clcgh.org Building The Capacity Of Christian Leaders, Equipping The Saints For The Work Of Ministry, Redirecting Straying Christians To The Sound Knowledge Of Christ

One comment

Pingback: Why Churches Must Unite To Fight Against Clericalism (2) | Christ-Conscious Leadership Centre